Good Grief! (Or, Drawings from Yet Another Neighborhood)

Even as Gorey’s works, specifically the works included in the 2021 House Exhibit Hapless Children, skirt around a solid answer as to whether they’re for kids or not (Gorey said “Of course” while his publishers said “No way”), it seems evident that his books were the harbingers of change in Children’s Literature that began in the late 1950s and continued through the 60s.

We’ve discussed in recent exhibits the effect that The Doubtful Guest had on illustrators like Maurice Sendak and Chris Van Allsburg (among others). Published the same year as Dr. Seuss’ The Cat in the Hat (1957) both books succeeded in introducing chaos and tension into the vocabulary of children’s books. If Gorey worked in a vacuum, it was a rather porous one. The works of Edward Lear resonated with him from an early age, and he certainly absorbed (and frequently illustrated) the occasionally disruptive children’s verse being created by his former Harvard professor John Ciardi. Sendak, protégé, competitor, and friend to Gorey, felt close enough to call him “Ted” which was a moniker generally only used by family members. While Roald Dahl started creating children’s work with a darker external sheen (and occasional patinas of misogyny and antisemitism) in Britain through the 60s and beyond, it was really the success of Daniel Handler’s Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events franchise (a 13-book homage to Gorey starting in 2000) that showed how Gorey’s construct of a dangerous child’s world—roughly about thirty years ahead of its time— had finally found acceptance in publishing circles.

Yet for all the name-dropping comparisons above, there is another important creator of Children’s Literature whose trajectory most closely parallels Gorey’s; two uniquely different artists whose careers both involved the drawing of, and the drawing from, the experiences of childhood.

Charles M. Schulz (the beloved creator of the Peanuts mega-franchise) and Edward Gorey (whose website you’re visiting) are rarely seated even remotely close at the same table, but it’s worth ruminating over some of the interesting parallels that connect these two artists: Both were only-children born in the Upper Midwest (Schulz in Minneapolis in 1922, and Gorey in Chicago in 1925), both skipped ahead two grades while in elementary school, both endured family disruptions at impressionable ages (Gorey’s parent’s divorce and Schulz’s mother’s early death) both came to full-flower artistically at the same time (the 1960s—including the years leading up to and just after), and both died within two months of each other in 2000.

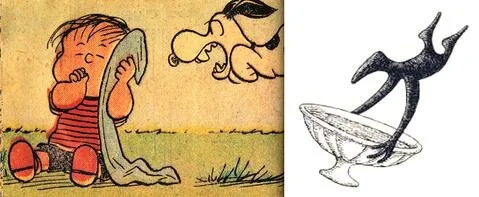

Schulz, whose commercial success will likely never be surpassed, certainly overshadows Gorey’s somewhat respectable successes, but they remain co-instigators in a major shift in children’s literature. Schulz inspired countless cartoonists, and Gorey a multitude of illustrators, to look harder at the complexities children face. Both artists suggested the possibility that happily-ever-after no longer needed to be a given. There were now shadowy corners of the yard where stories could unfold; there were days where it stayed cloudy and raw. Linus mistakes his first snowfall for nuclear fallout, Neville succumbs to ennui. While watching a kite being eaten by a tree seems different from seeing Kate struck by an axe from heaven the effect, to an impressionable child, is probably the same. Schulz wasn’t scared to insert bits of scripture into his strips, Gorey hid Corinthians chapters in the license plates of malevolent sedans. Both artists opened doors to worlds of random violence and cruelty. Gorey’s Figbash character (whom he somewhat appropriated from Man Ray) seems an unintentional parallel to Snoopy, though Schulz lets you in on Snoopy’s aspirations and fantasies. Figbash forever remains an inscrutable character, its interior world tightly sewn out of sight. Both characters speak volumes about their creators.

Largely because of Schulz’s and Gorey’s work, children’s literature would now concede that some things are indeed scary, and some things might always hurt. Here were characters informing you that there would be pain and failure and humiliation and that you could expect to find yourself on both the receiving and giving ends of all of them. In somewhat inverse ways, both artists’ work instruct children about the menace that they would soon encounter. Schulz utilized a very minimalist world of curb, lawn and fence to present a very complicated world described by children in adult voices. The complicated world as created by Gorey, rendered in heavy crosshatching and suffocating décor, is adult and brutal—but described in the simplicity of children’s voices.

Though working from opposite approaches, and from opposite coasts, both Schulz and Gorey created art containing the same message: that it was okay to let children know that there would be grief that would linger—but that there was such a thing as good grief; that grief could sometimes become a rich loam from which observation and self-reflection grew; that not only were the threatening things that hid in the dark recesses of a room entirely imaginable, but also into that same darkness one would sometimes return—to find solace.