Cutting Along the Lines: Edward Gorey’s Paper Dolls

This blog was written as part of a series on Moveable Books. To learn more, take a look through our 2024 exhibit Exquisite Corpse: Edward Gorey’s Moveable Books.

Paper katashiro from Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 animated film Spirited Away. Papercuts omitted from the final release.

The paper doll, thanks to its relatively low production costs and accessibility, has been scattering cut-out scraps across human history for generations. The Japanese katashiro, a simple paper or wooden doll used to rid oneself of bad luck, is a tradition that goes back to at least the seventh century. The Hina Okuri and more recent Hinamatsuri festivals both involve the construction of similar paper figures for nagashibina, or floating the dolls down the river. The hina okuri tradition itself is over a thousand years old.

A French pantin of a harlequin from the late 19th century. No need to fuss over drawing hands if you make your sleeves extra-long. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In Europe, the much younger industry originated with the jumping-jack doll. The 18th century French pantin was massively popular with the upper classes in particular. These jumping-jacks were often designed to poke fun at celebrities or character types and came with specific accessories — though, tragically, with no extra outfits. From the midcentury onward, paper dolls were adapted by the German, English, and French fashion industries as cheap, accessible ‘models’ for their designs. The invention of lithography in the late 1700s coincided nicely with the advent of the children’s book industry, which meant more dolls for a wider audience. The idea of cutting out paper dolls didn’t come about until the Bilderbogen, a German invention of full sheets of designs printed on cheap paper, and from there, the children’s market really took off. In the early 19th century, paper dolls began to be sold with miniature ‘chapbooks’ of moral fables intended to guide children in the right-thinking direction. Whether children actually absorbed any of this or were simply delighted to torment their paper victims is up for debate.

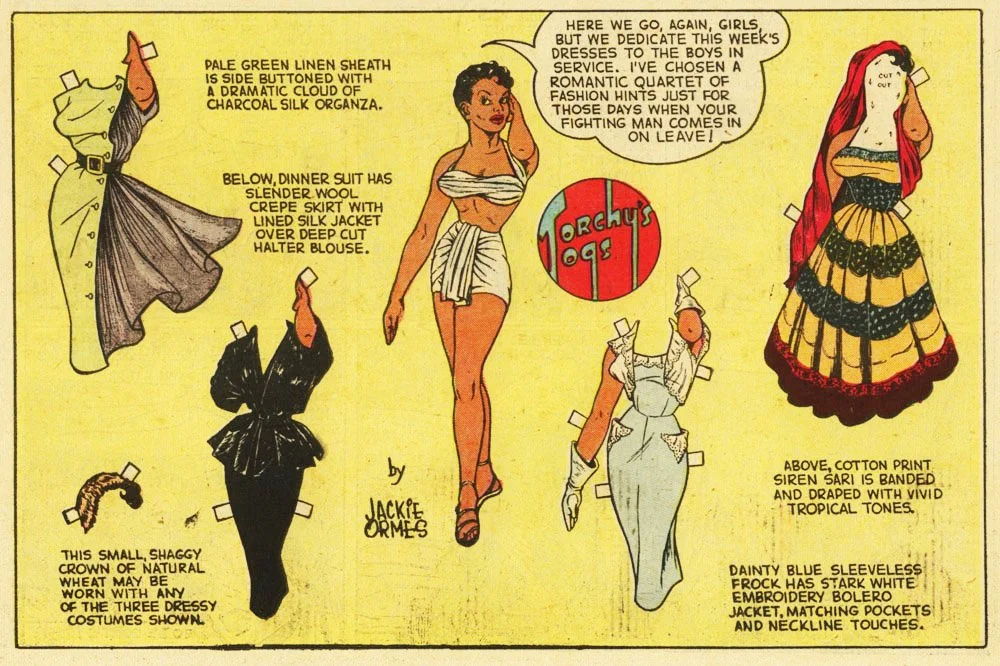

The many outfits of Torchy, a recurring paper doll character by Jackie Ormes. ‘Fashion Hints’ is a pretty modest way of describing a wardrobe that wouldn’t look out of place on any modern red carpet. Courtesy of DeeBeeGee's Virtual Black Doll Museum.

The medium saw its peak in the mid-1800s to mid-1900s, where they served roles as toys, advertisements, luxury gifts, and even political propaganda. In the US, newspapers would publish weekly ‘fashion plates’ for readers to cut out and enjoy. Many American dolls followed their 19th century French predecessors and became full characters, with some tackling topical themes of feminism and racial injustice. No small feat for ink and paper — but then again, the scissors and dotted line are mightier than the sword.

An unreasonably smug-faced promotional doll for New York general supply shop E.S. Burnham Co.’s “Hasty Jellycon” — so simple “a child can make it.” No comment on the Cream Toast with Clam Bouillon special. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth.

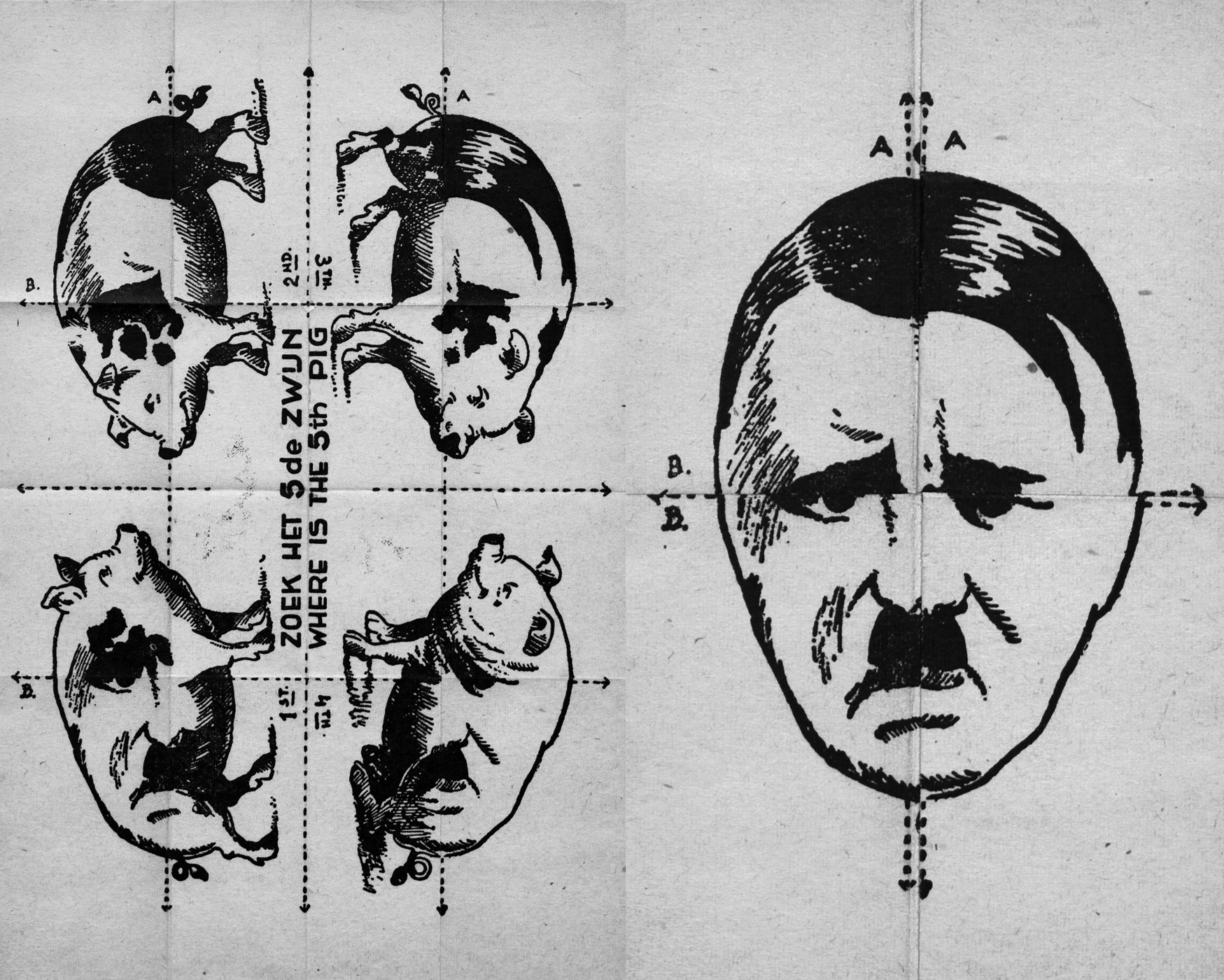

A delightfully pointed anti-Hitler fold-out from the Netherlands. The four pigs look appropriately pleased about their role in denigrating the fifth.

From religious objects to advertisements to political propaganda to children’s toys, the customizability of paper dolls means that pretty much everyone can — and does — find a use for them. Edward, who treats the Book as an optional format, was an inevitable fan. Edward’s exploration of children’s literature subverted as many expectations as he could reasonably manage. To put it simply, we like to think of his work as adult books written for children — though adults, as is our wont, wedge ourselves in too. Looking back to our 2021 exhibit, The Hapless Child (1961) is a stellar example of Edward’s talent for translating the horrors of adult life into a format accessible to (and mostly enjoyed by) children. The titular Child, one Charlotte Sophia, is introduced to us as well-loved and cared for. By the end of Edward’s tale, of course, she is left a pitiful creature stripped of every joy in life (not to put too fine a point on it), before succumbing to an early and deeply tragic death. The 1810 paper doll (and accompanying moral tale) The History of Little Fanny follows a similar plotline. Little Fanny, too, is raised wealthy, but unlike Charlotte Sophia her punishments are born of her sins. Fleeing from home after a tempter tantrum, she becomes a destitute street urchin, wandering the streets mourning her old life. Upon praying and repenting, she returns home to her joyful and loving mother. The consequences of vanity and laziness, the young Regency child is told here, are both severe and warranted.

Edward is, of course, no stranger to lifting imagery and ideas from artists and mediums he enjoyed. The dramatic moralizing of many a nineteenth-century children’s story — think Der Struwwelpeter — is a frequent canvas for his tales of woe. Little Fanny is, in many ways, the Platonic ideal of the European paper doll: she sins, she suffers, and she is rewarded for learning from her trials. Simultaneously, Little Fanny offers the young reader an introduction to the revolutionary format of the moveable book. These two forces — a not-quite-traditional art form and the uncomfortable grimness of childhood — are creative catnip for Edward. In fact, one wonders why he didn’t incorporate Charlotte Sophia into her own paper doll book. Instead, he created E. D. Ward: A Mercurial Bear (1983) where, with a pair of scissors and a total disregard for what you just paid for the book, the cover image and interior pages are cut apart to dress the bear in several outfits (or accessories like gloves, shoes, hats, and feather dusters). There are plaid suits, ballerina attire, Medieval combat garb, sailor suits, and bulky sweaters emblazoned with a “Pomplamoose.” One of the outfits seems to be that of a bear—but a different bear. The only thing that really seems mercurial about E. D. Ward is their swiftly alternating gender presentation.

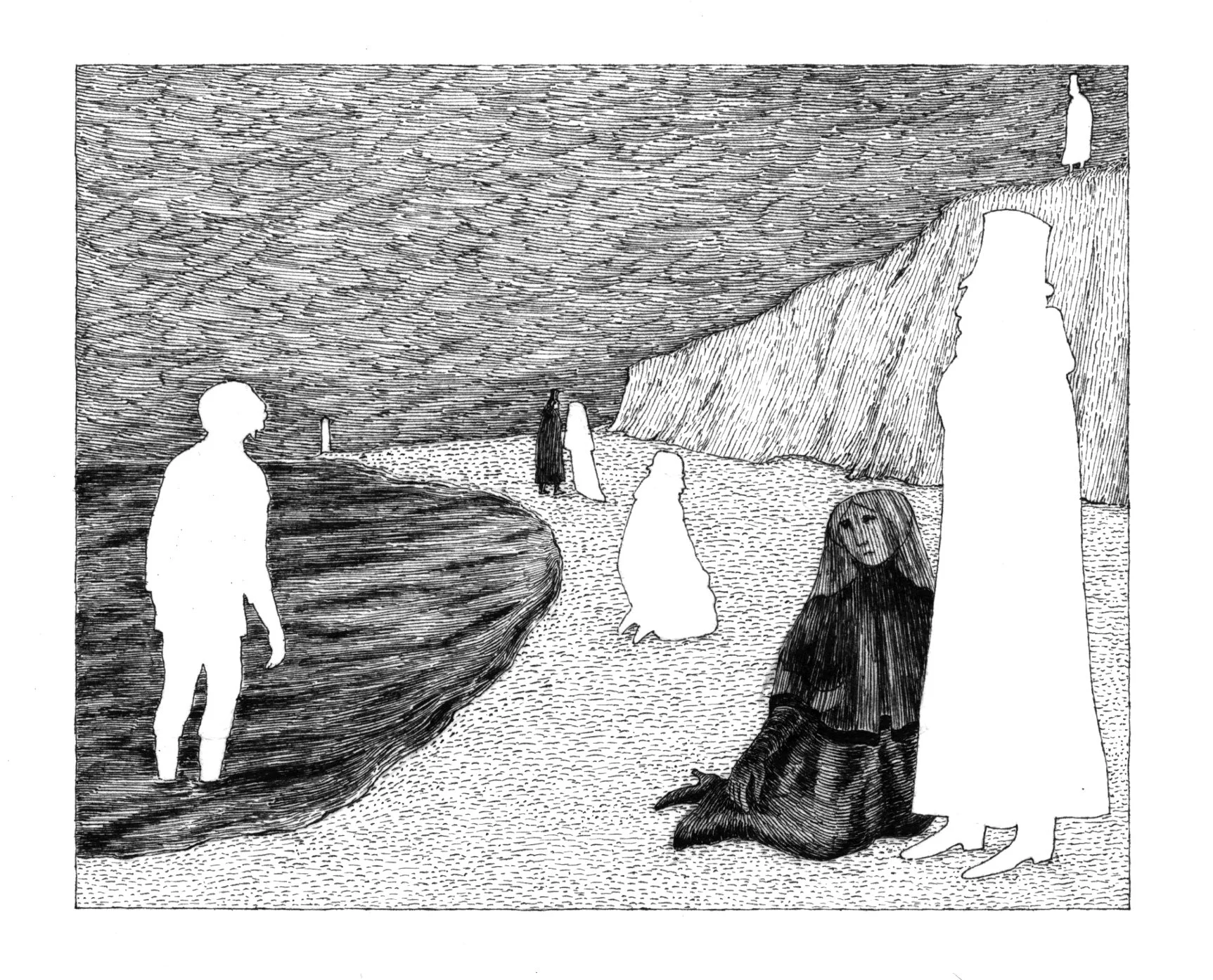

Intriguing fragments of a book Gorey started over a decade earlier than E.D. Ward indicate a paper doll format—of sorts. The Haunted Blancmange (1972) is an unfinished work (four drawings and cover were completed) that plays both as a paper doll cut-out book and a rumination on loss, memory, and absence (again, the absence of things always comes into play in Edward’s books). We included these drawings as part of the He wrote it all down Zealously exhibit of 2020. When viewed then—in the midst of the Covid epidemic—the drawings became chilling and mournful plays on isolation and distance. They continue to be.